Safety first

- Dimus

- Jul 31, 2025

- 26 min read

Engineer's notes

You don’t have to fight for cleanliness; you just have to sweep.

You don’t have to fight for safety; you need to think first and then act.

In March 2005, an explosion at a chemical plant in Texas killed 15 people and injured 180, and about six months later, we in Talbot were reviewing the incident with the Health and Safety Committee under Larry Hogan. It wasn’t that there weren’t enough incidents of our own, but it was a particularly egregious case, and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) sent out inspection and investigation materials to major chemical companies for review. British Petroleum had built a distillation column at its refinery plant to separate the gasoline fraction of oil refining into high-octane and regular gasoline. The installation was not small by any means: almost three meters in diameter and fifty meters high. The initial stock mixture is separated by evaporation: the lighter-boiling product comes out of this monstrous pipe at the top, and the high-boiling product at the bottom. At 2 a.m., they turned on the pump and began feeding liquid into the column.

The production site was modern – all the equipment was automated and monitored from the control room by operators watching what is happening on large displays. An hour after the startup, the control program was supposed to open the bottom product valve so that it could flow out of the column, and that is what happened. A green “OPEN” message appeared on the screen, and as was written in the initial British Petroleum report after the incident, the operators, there were two of them, decided that everything was fine. In fact, there happened to be a manual valve on this line that they forgot to open, and despite the green signal, the liquid could not flow through the pipeline and began to accumulate in the column. This forgetfulness is called the “human factor”.

At 6 a.m., a new shift arrived and did not notice anything bad, although a red sign was flashing on all the monitors: “ALARM! Liquid level in the column is above the permissible limit!”, which was turned off, for some reason considered false. At 10 a.m., the 50-meter column was filled to the very top, and the liquid - hot gasoline - flew into the general ventilation system of the refinery plant at a rate of about 500 liters per minute, where it partially evaporated. And three hours later, in the utility yard, located half a kilometer from the ill-fated column, the truck driver turned on the ignition and everything detonated...

***

In Talbot’s research center, in every space between windows and doors, in conference rooms, labs, and the cafeteria, “Our Vision and Values” were posted in neat frames under glass. The list of values began with the statement “Safety first!” - not the interests of shareholders, not profit, not even the quality of the product, but the safety of workers above all, implying that the company would spare no effort or expense on safety precautions, which turned out to be true.

The second slogan was “Drive to Zero! All incidents are preventable!” meaning that all accidents can be avoided with the right measures, and the Company strives to have the number of these incidents equal zero. After that came the declaration that each employee is responsible for his own safety as well as for the safety of all others, followed by the incantations about quality, wasteless production, environmental protection, resource conservation, and devotion to the interests of the consumer, but here we will limit ourselves to safety, since nothing is more important. To the credit of the author of the "values", we note that ‘diversity’ and ‘equity’ were not yet openly mentioned.

It must be said that chemistry is a dangerous thing in general; there are poisonous, toxic, explosive substances, mechanisms with teeth, motors, hot surfaces, high pressures, high voltage electricity, and compliance with safety precautions for everyone involved is a very important matter. Therefore, you should never forget about safety, both your own and those around you, and everyone who will carry out your work instructions. The description of any working procedure is always preceded by a chapter listing possible dangers: what not to do and what to do in case something goes wrong: overheated, over-poured, under-mixed. Surely, everyone wants nothing bad to happen, no incidents:

- How many safety incidents were there in your department in the reporting year, Comrade Chief Engineer?

- Zero, Sir!

- Great! Get a bonus and keep up the good work.

Oddly enough, a good slogan “Drive to Zero!” leads to the opposite results: it does not matter whether there were any safety incidents during the reporting period or not - you cannot relax, and in this case, the Machiavellian “Demand the impossible - you will get the maximum !” does not work. For example, in the third half of the year, there were no registered incidents at the plant, and this means that everything is fine, the people are trained, there are no safety violations, and it will always be like this. - It will not! - People tend to make mistakes, even the most knowledgeable and experienced, and these mistakes can be absolutely, well, almost, random.

Here I am, Wan Durago, the head of a technology lab with thirty years of experience and having seen all sorts of very unpleasant incidents, sometimes with fatal outcomes, conducting a routine experiment - distilling ethyl alcohol in a small rig assembled by my own hands. My employees are busy with other projects, and I’m even glad that I’m doing it myself, since it would take a long time to explain what data I need to get to optimize the process. Not to sound like I’m grouching—because I don’t think young people get everything wrong.

I prepared a solution: four liters of 80% alcohol in water, poured it into a glass flask, and turned on the heat - you need to bring the mixture to a boil, which usually takes a quarter of an hour. While I was reading some documents, twenty minutes passed - it didn’t boil, another five minutes - nothing. The temperature is correct, but it doesn’t boil, probably uneven heating, but there is no stirrer - you can do without one for such a small setup, and then a “good idea” occurs to me: throw “boiling chips” into the liquid.

Boiling chips are porous stones that, when added to a liquid, release air and initiate boiling when heated, of course. Every sophomore chemistry student knows this, as well as the fact that these chips must be added in advance, while the liquid is cold. And your experienced engineer, in some kind of confusion, took out the glass stopper, threw a pinch of this magic stuff into the hot mixture, and closed it back.

The distillation apparatus was not pressurized and had, as it should, a small tube to allow the vapors to escape, just as when water in a kettle boils, the vapors begin to escape through the spout and nothing explodes, but in my case the liquid boiled instantly and so much vapor was formed that the glass stopper shot up to the ceiling and a stream of boiling liquid flew out of the hole.

There were three good things about it: first, the boiling mixture didn’t spill on me, second, the glass flask didn’t explode - I didn’t plug it properly, and third, no one saw this disgrace: I hid it for twelve years, but I can’t anymore. Well, the bad thing was that the hot alcohol mixture flashed on the electric stove on the laboratory table, a fire started, and the experiment had to be stopped.

After a slight shock, I pulled an asbestos blanket out of a special bag hanging on the wall, covered the table with a fabric, and the fire was extinguished. Then I turned off the electric heater of the column, put things in order, and sat down to rewrite the work instructions, adding a paragraph that before pouring the initial alcohol mixture into the heating container, five grams of boiling chips should be loaded there. I decided not to tell anyone about the incident - I would have fired such an employee.

***

I spent my first thirty days at Talbot reading corporate policies and manuals, all in electronic format and with a mandatory quiz at the end of each document. Starting with “Our Vision and Values,” it covered everything from submitting invention applications and filing reports to rules for labeling samples and booking business travel tickets, as well as a selection of the most important directives, of which I remember “banning the use of organic solvents in developing new processes” - how could chemistry be without solvents?, and “removing from circulation devices called nigrometers,” which were used to measure the blackness of carbon soot, the company’s main product; political correctness was just gaining ground.

There was naturally a plethora of documents concerning all aspects of safety; the company, after all, was a chemical one, but the philosophical basis was represented by two systems, or rather religions, called STOP and 5-S. 5-S stood for Sort, Set in Order, Shine, Sustain and Standardize and was constructed from recommendations invented in Japan for the work of a mechanic or turner, aimed at maintaining order in the workplace: drills in special cells by size, bolts and nuts in labeled boxes, as in the famous joke about the old conductor who hid a note in his tuxedo’s pocket: “Violins on the left, cellos on the right .”

The STOP program came to Talbot from the famous American chemical company DuPont and was intended for mutual verification of compliance with safety regulations, when each employee is not indifferent to how and what others do: two minds are better than one. Later, I will tell you how this was applied in practice, but for now, I passed all the electronic exams and was admitted to engineering work in the Department of Special Products, manufactured on the basis of Talbot soot, 90 percent of which goes to the production of automobile tires, which is why they are black. Special products included all sorts of black paints-pigments, toner powders for laser printers, and some materials for electronics, in particular for liquid crystal displays, where, unlike tires, the degree of blackness was very important, but there was nothing to measure it with; the nigrometers were thrown out in the dump.

I reported my readiness to director Kevin Massila, whom I really liked for his Finnish efficiency, goodwill, and calm. When I subtly noted that I had never seen such a level of attention to production safety, he sighed slightly for unclear reasons and immediately invited me to join the Safety Council of our department, to which I, of course, agreed.

The head of the Special Products research department, and Kevin’s boss too, was a Frenchman, Greg Colette, a very friendly and charming man, whose charisma I fell under immediately after his first phrase:

- Well, Wan, are you having fun here? - a little taken aback, I mumbled something affirmative, and Greg continued.

- That’s great, the main thing at work is to have fun! And Wan, considering your diverse experience and excellent recommendations, I want to bring you onto our Safety Committee.

- But Kevin already included me in it...

- No, this is the Talbot Corporate Safety Committee, and the sectional council is at a different level. And don’t doubt, Wan, it will be fun! - And so, it turned out.

***

After some time, I was appointed head of a three-person technology group, and we were improving the dispersibility of soot in water by chemically modifying the surface of its particles. No matter how hard you try, you can’t avoid getting dirty when dealing with soot, and I remember my work at Talbot as a “black” period in my life. Chemistry is generally a colorful science, I had a “white” period of work at the Waters company with silicate polymers like silica gel – white powders, “orange” years at the Dutch DSM, where they made yellow-red carotenoids – natural compounds responsible for the color of autumn leaves, salmon, tomatoes and egg yolks, and later a “green” period at a startup with the pretentious name of Joule Unlimited, where under the slogan “Pigs can fly” they tried to force green algae to produce ethyl alcohol. We pumped emerald-green biomass tirelessly through reactors transparent to sunlight, but it didn’t work – the alcohol mercilessly killed the algae cells, and the poor piglets were never able to take off the ground, but I already wrote about this (The Battle for Ethanol).

There was a lot of work, in addition to laboratory experiments in the research center itself, we conducted experiments at a pilot plant in the neighboring city of H on a much larger scale and had to deal with quite dangerous substances such as hydrochloric, nitric and hydrofluoric acid, and the soot itself, like any powder, could explode under certain conditions; it is carbon, and reacts very well with oxygen in the air. Before starting any experiment or process, it was necessary to write the most detailed instructions, including a mandatory chapter on safety measures indicating all possible damaging factors: chemical, physical, mechanical and biological, and what to do when something went wrong: a device failed, a toxic liquid or gas leaked, or the wrong valve was opened by mistake and the entire batch from the reactor flowed into the sewer: this happened and was not uncommon.

The correctness of all procedures had to be checked and approved by a specially appointed commission, and then I, as the head of the laboratory, had to instruct and train the technicians and junior engineers who had actually to carry out the process. All this certainly necessary bureaucracy took a lot of time: try to gather in one place the head of the pilot where the experiment is being conducted, the safety manager, the chemist who developed the main reaction and a representative of the analytical laboratory - what kind of experiment is it without taking and analyzing samples, and then spend several more hours reading them your written procedure and answering questions.

When a seemingly simple laboratory experiment of two or three stages is planned: heat – stir – cool, safety meeting can be possibly finished before lunch, but if we are talking about putting into operation a small installation with a dozen devices and a hundred instruments, then the session of the safety committee can drag on for a long time: I had to participate in a meeting lasting three weeks, and in order to keep those present from being distracted, it was necessary to lock the doors and take away mobile phones. All participants, usually mid-level managers, have a lot of responsibilities and a continuous flow of questions requiring an urgent response, and in order to somehow move the process forward, a mediator, Gary, is invited from the outside - a consultant of retirement age, who, perhaps, understands industrial safety, but does not know our production. As a rule, I tried to meet with him one-on-one before the start of the committee and tell him what we are doing, how and why, and give the necessary explanations on the chemistry and equipment, but if this could not be done, then the procedure became purely formal.

- What will happen if the pressure in the T-22 tank drops below atmospheric? - asks the mediator.

- Nothing,- I answer,- The T-22 is designed for a full vacuum, aka zero pressure.

- Okay, - says Gary, putting a check mark in a special questionnaire table, and all the participants nod in good spirits.

- What will happen if the pressure in the T-22 tank increases above the permissible level?

- The M-2204 safety valve will open and release pressure, - I answer, and we move on to the next piece of equipment...

- What if the safety valve doesn’t open, Dr. Durago? - Director Massila, my boss, suddenly intervenes.

- Then, - I have the answer ready, - at a pressure of five atmospheres, the rupture disk M-2208 on the tank will burst and open the line C-316, and the excess gas will flow into the buffer tank T-45. - Kevin is not satisfied:

- What if the rupture disk doesn’t burst?

In this case, the operator’s screen will display a red message: “Critical pressure in T-22! Evacuate the building!” and in thirty seconds, the iron barrel T-22, the size of a bus, will explode, and shrapnel will fly two hundred yards around. But I’m hesitant to say this, and here Gary comes to the rescue:

- Kevin, this would be a “double jeopardy” - both the valve and the disk would fail at the same time, and according to the rules of analysis, we do not consider such options. - Everyone agrees, and the meeting continues.

According to statistics, the probability of double and triple failures is far from zero, so additional levels of protection are introduced, like in war: the enemy has broken through the first line of trenches, and behind it a minefield awaits him, and then an anti-tank ditch, and then a mined bridge. Everything was foreseen, but it turned out that something had to be entrusted to people, and humans are prone to mistakes. At the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, there were as many as seven levels of protection, but Moscow physicists really wanted to conduct a special experiment and turned the whole thing off, and well, you know what came of it. The bridge was mined, and when the enemy approached, it turned out that the guard had gone out to relieve himself.

***

Already on my first day at Talbot, I found mysterious appliqués of colored rectangles on my office desk, and the first thought was that the desk had previously been used in a kindergarten. But after lunch, during the introductory briefing, I was informed that this is how the 5-S program is implemented, and each rectangle indicates the place where a certain office supply should be: the largest one is for the computer keyboard, a smaller ones are for the mouse, for the lab notebook, for scissors, pencils, and a tiny one is for an eraser.

My mentor, our group chemist Eugene, explained that order in the workplace increases productivity and work safety, and my job is to lay out all the supplies in perfect order, sign all the rectangles, using provided stickers (“Keyboard”, “Mousepad”, “Rubber”, etc.) and invite the 5-S Commission for verification. They will take a picture of the table and the room, and it will be called the “Basic Standard,” and the photo will be framed and hung on the wall. The Commission can come and inspect at any time, and if anything is out of place, they can impose a penalty, and the photograph of the mess will be posted on the notice board at the entrance to the building.

Eugene then led me into a small conference room where eight chairs on wheels were arranged around an oval table. Opposite the arms of each chair on the table were two vertical stripes: “LEFT HAND” and “RIGHT HAND.”

- After each meeting, everything must be in perfect order. There are six permanent members in the 5-S Commission, and checks are carried out frequently. - Then he laughed and added:

- Recently, a terrible mess was left in one of the rooms - and two extra chairs were also found! The 5-S commission began a burning investigation, and then it turned out that the Company’s Board of Directors was meeting there.

We giggled together, and I thought that I wouldn’t last long here: it’s not that hard to confuse the left and right hands.

***

Luckily for me, the Safety Council, where Kevin Massila sent me, did not deal with the 5-S program, and I did not have to go from room to room, arranging chairs in order and sticking menacing signs on the tables: “Scissors” and “Stapler”, but even without this, the Council had more than enough work. The main task was the implementation and control of the STOP program, which was personally supervised by Talbot’s VP of Compliance, a very nice, pink-cheeked, gray-haired old man of about sixty, Herbert Snow. Every company must comply with a certain set of rules established by both federal and local regulatory agencies, and someone must monitor these regulations. This includes ensuring workers’ rights, environmental protection, fire safety, preparedness for crisis situations such as nuclear war, and, of course, safety. Dr. Snow’s main passion was the promotion of Talbot’s “Values and Visions”, and his second was STOP.

The point of the STOP program was that every employee monitored the observance of safety rules always and everywhere, especially by other employees. Exempli gratia, you are walking along the territory of a chemical plant and see that a worker welding a steel beam at a height of ten meters has his safety belt unfastened. Stop and shout to him: “STOP WORK! Fasten your f..ing belt, and you can continue! “Then go to your office and be sure to enter this case in a special “STOP database”, classifying it by the nature of the violation, the seriousness of the incident (after all, he could have fallen from surprise), time, location, but in no case identifying the wrongdoer - you can’t offend a person.

When I came under Snow’s command, he observed me for a long time, silently and thoughtfully, smiling, slightly stretching the brush of his gray moustache, and then asked if I could take control and analysis of the contents of this database and present a report at the Council meeting every quarter. I agreed - what’s difficult about that, it’s even interesting.

- That's great, - said the vice president, - and don't forget, Wan, that you, like every engineer in the company, must log at least two STOP observations a month. This is, ha-ha, a condition of employment here.

***

My lab was in a state of permanent emergency: a certain client urgently requested 40 kilograms of our modified soot for its tests, and we had only a small two-liter reactor for this purpose, which could only produce one kilogram per day. The client's wish is the law: two of my technicians worked on this reactor in 12-hour shifts, and we, together with my third employee of Italo-Albanian origin named Gezim Merzini, frantically tried to set up and start up a 30-liter reactor, since according to rumors, the client would soon need another hundred kilograms. Gezim was a knowledgeable person, and I routinely relied on his professional judgment. However, the very fact of my management still irritated him, as in Albania, he was an engineer, but in America, for some reason, he did not advance further than a technician. I took on the responsibility of writing all technical documentation for the reactor, operation procedures, and, of course, safety.

All the necessary Talbot’s protocol on process safety was certainly fulfilled: the instructions were approved by the commission, the workers signed where necessary, and we did the required precheck of the equipment before starting work. It must be said that the installation and the process itself were, as they say, "not for beginners": there were enough dangers, and the substances were so poisonous and volatile that it was necessary to work in special protective suits and gas masks. It turned out that Gezim has weak lungs, a doctor's note about it, and cannot work in a gas mask, so I had to carry out the experiment together with another technician, Mike, dressed, as required, in a suit and mask, as I was trained in the military department of our chemical institute.

It seems we had foreseen everything, but evil fate, disguised as the human factor, once again prevented us from achieving the coveted "Zero" and reporting absolutely safe performance with zero accidents. When the reaction, which had lasted three hours, ended as expected, and all the sensors for the presence of toxic substances in the air lit up green, I gave the command to remove the gas masks, and that’s when Gezim popped out like a jack-in-the-box, ready to help unload the product from the reactor.

We placed the trough underneath reactor, tilted it at a 45-degree angle, and slowly unscrewed the side cover – nothing spilled out. Mike, according to protocol, started the reactor's internal mixer, similar to a screw in a meat grinder, at low speed. I turned away from the reactor to make a corresponding note in the log, and suddenly there was a scream. It came about that Gezim had stuck a small stove poker into the reactor to "help" the powder spill out: the thing got wrapped around the mixer and hit him in the arm with its end. While Mike was turning on the motor, Gezim ran off somewhere to get this stoker. The blow was not strong, but a blueish bruise appeared on his forearm. Mike took the guy to the hospital, and I informed Kevin Massila about the partial success. I then poured the product from the trough into a special bag and sat down to write the Incident Report.

***

It was approaching the end of the month, and I was having lunch in the corporate cafeteria with Eugene, my former mentor, with whom I had somehow become close due to our shared country of origin, and who occasionally offered me advice on internal departmental relations and the general political situation.

- I hope, Wan, you've already made the two required observations on STOP?

- No, Zhenya, thanks for reminding me, tomorrow I'll go to the labs and have a look – maybe I'll see some violations.

- Tomorrow is Saturday - a non-working day, and Monday is already the second of the next month. I advise you to enter the records into the database today before five, if you don't want to deal with Herb, and you don't.

- I understand, but I have a meeting starting now and lasting right before the end of the working day. I won't have time…

- Then write down at least something... Look, a comrade has poured himself a cup of coffee and is carrying it to the office, but he hasn't closed the lid.

- So what?

- Without a lid, he can get scalded by coffee, and that's not safe. You can certainly warn the guy and remind him to follow the rules. But it's better not to disturb him; otherwise, he really will get scalded. - We left the dining room and moved along the corridor, following the coffee lover.

- Hey, he's a serial offender! - Eugene suddenly cried. - Look!

- What's wrong with him now?

- What do you mean? He's going down the stairs and not holding onto the railing! This is a gross violation of safety regulations. He's lucky Snow can't see him. Write it down, Wan, now you have two STOP observations: " At 12:52, N was going down the stairs from the second floor of Building 4 without holding onto the railing. I stopped N and explained to him the danger of ignoring safety regulations - he could slip and break his leg or arm. " Don't forget that identifying the violator is prohibited.

***

The agenda of the next meeting of the Safety Council included three items: the incident in the analytical laboratory, the incident in the technological laboratory with Gezim, and the verification of the implementation of the STOP program.

During an inspection in the analytical laboratory, a young specialist discovered that someone had spilled liquid on the table and no measures had been taken. In fact, no one was in the laboratory at that time, and she wrote a report. The head of the laboratory, Lena, who was invited to the meeting, took the incident seriously: approximately 20 milliliters of distilled water had been spilled, but water is a chemical substance and spilling it is unacceptable. The report was followed by an analysis of the causes using the "5-Why" procedure adopted in Talbot. It was necessary to get to the root cause, asking questions and answering them, filling out a special form that Lena voiced at our commission. Snow closed his eyes and seemed to fall asleep.

- Why (#1) did the liquid spill? - The lab assistant carelessly tilted the bottle over the table?

- Why (#2) didn't he cork the bottle? - Because he opened an empty bottle at his workplace and came across a column of distilled water standing on the table without a stopper.

- Why (#3) did he come without a stopper? - Because it wasn't in the instructions for transferring liquid.

- Why (#4) wasn't this in the instructions? - Because there were no instructions written for this operation.

- Why (#5) were there no instructions? - Because collecting and carrying distilled water was not considered a dangerous operation.

Lena took a stab at preparing the said instruction within two weeks. The presiding Herbert Snow nodded his head favorably, praised the young specialist for the important STOP observation, and expressed the idea that excessive vigilance would not hurt: today it turned out to be water, and tomorrow it might be sulfuric acid.

This madness lasted forty minutes, and I relaxed somewhat in anticipation of the investigation of my incident. Naturally, I wrote an incident report, mainly trying to justify Gezim's reckless action by citing the fatigue and intense work of building a pilot reactor in the shortest possible time, assuming he was in danger of a serious penalty. To my surprise, Snow did not let me talk but read out a report from Merzini himself. It turned out that it was I who had given him the instructions to stick the stoker into the reactor with a rotating stirrer. The old intriguer Snow's moustache bristled with joy, and his rosy cheeks acquired a crimson tint; he had read my report but had not warned me of the existence of this note and was now watching how I would take the blow.

Neither Gezim nor Mike was at the Council meeting, and I, practically speechless, stammered that in that case we should ask Mike. Snow graciously agreed: the showdown was postponed for two weeks, and he moved on to the third question about fulfilling observations under the STOP program. I was in a daze. At the end of the discussion, my name was mentioned again, and it dawned on me that in two months, Wan had to present a report analysis on the STOP observations accumulated in the database over the past two years. I had not looked at it yet.

***

At the morning meeting, Greg Colette introduced us to a new chemist, his namesake Greg Miller, who had previously worked at DuPont, one of the most famous chemical companies. The company's founder, Monsieur du Pont de Nemours, started his business in America with the production of gunpowder and dynamite, and then DuPont went down in history with its discoveries of Nylon, Teflon, Neoprene - synthetic rubber, Freons for refrigeration units, and Kevlar for bulletproof vests. However, the "peak of achievements" was conquered in 1979, when DuPont introduced the STOP program at all its plants, which has already been written about in our history. Greg turned out to be a very sociable guy. He was given an office next to mine and included as a chemist in our group, which was developing water-soluble soot. I began to introduce him to the course of business, of course, after he completed a 30-day training.

On Eugene's advice, I informed Greg Collett about what had happened at the Safety Council and Gezim's report, as my boss, Kevin, was on vacation.

- Now, Wan, you have fun, my friend. - The vice president responded.

- Don't worry, this is a common practice in Talbot. I'll take care of it. Relax and work tranquilly.

That was our last conversation – a couple of weeks later, I learned that Colette had been transferred to Louisiana as the director of the local Talbot plant; perhaps his knowledge of French played a role. But he apparently sorted things out with Snow – the stove poker incident was forgotten, and I didn't have to explain myself anymore. According to rumors, Mike didn't confirm the vile slander of Gezim, but the latter remained in my group. For some time, he was on vacation, then on sick leave, and when he returned, he ceased working completely, sitting in the utility room and reading Internet news on the computer. I didn't bother him, and the 30-liter reactor was never turned on again – our client's plans changed.

***

The Safety Committee, where, as you may recall, Greg Collett put me in charge, unlike the Safety Council, met irregularly, but rather as needed, when something happened at one of Talbot's 32 plants scattered around the world. It was presided over by Larry Hogan, an engineer hired by the company's founder, Jeffrey Talbot, who retired and handed over the reins to his son at the age of 102, around 1961. Larry had started as a worker at a rubber plant in Pennsylvania, when no one had even heard of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and his experience was not from books: he would simply throw a person off his Committee for talking about a spilled glass of water. He ignored the 5-S and STOP programs, despised Herbert Snow, and so his days in the company were numbered.

But for now, Larry was doing his job and analyzing safety violations, without bothering himself or others with any schemes like 5-Why, Root Cause, Fishbone diagram, or Fault Tree Analysis. And there was something to discuss - here is today's agenda:

- At a plant in Kuala Lumpur, a worker was unloading bags of soot from the back of a truck. The driver decided that he had finished and started moving. As he was leaving the warehouse, he drove under a fairly low arched gate…

- At the plant in Florence, after cleaning and washing, the reactor was mistakenly purged with nitrogen instead of air, and the wrong valve was opened. The inspector entered the confined space and lost consciousness. Two belayers climbed to pull him out and remained inside...

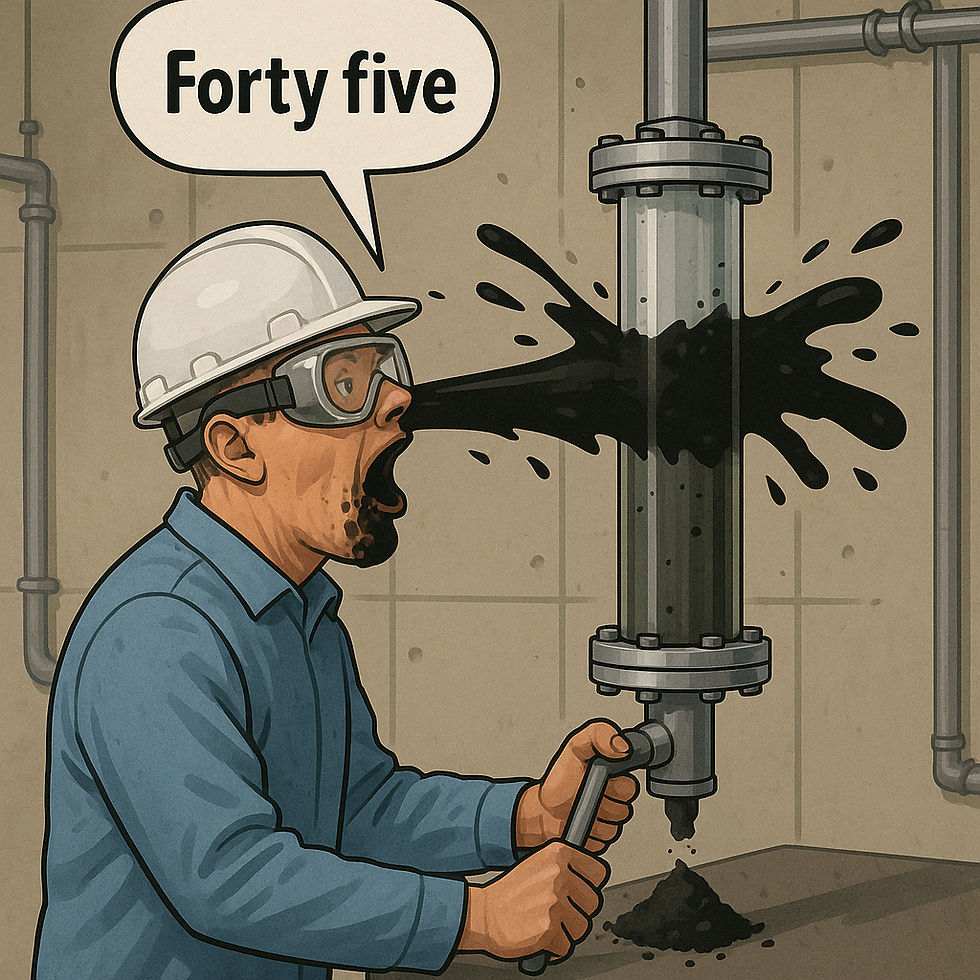

- Here is some local news from the Talbot's pilot plant, located not far from our research center. During the startup of the ultrafiltration unit, one worker slowly increased the feed rate of the pump, while another stood near the separation membrane, monitoring the pressure gauge and shouting out the result to the first. At the moment when the technician shouted, "Enough, forty-five!", the membrane burst, and a stream of aqueous soot solution, yeah, we did achieve good solubility, flew into his mouth under the pressure of three atmospheres. Soot is harmless to humans, but this was a test run, and in a normal process, there should have been nitric acid, which would have ended badly. The man was taken to the hospital, but after lunch, he returned to work. I was present at this incident as the lead engineer of the project and gave evidence to the Committee.

"Have you figured out the reason, Wan?" Larry asked.

- Yes, the membrane was cracked; apparently, it was dropped during transportation. The rest were checked - they are fine.

- Write in the operating procedure that when starting the installation, a special transparent safety shield must be put on the face. The pressure sensor must be turned 90 degrees so that the observer looks from the side. Next question!

There were no more questions, and Larry announced:

- We have a new chemist, Miller, from DuPont - invite him to the next meeting. Let him tell us how things are going with safety. And invite Dr. Snow, too. - It seemed to me that the legendary engineer smiled slightly.

***

Finally, I got busy with the STOP observation database: till now, I had only entered my two monthly observations there, and this time I used my administrative password and gained access to all the accumulated information. The very first request revealed that more than 15 thousand safety observations were registered, distributed by type as follows: about seven thousand “unclosed coffee cups” and slightly less than five thousand violations of “going up or down the stairs” - people just don't want to hold on to the railings! Eugene knew what to advise me. In third place were “unclosed desk drawers in offices” - a very nasty hazard, as you can trip and fall. Well, and then there were spills of all kinds of liquids and spills of powders, mostly black. I also received statistics on the time of observation: it is clear that the end of the month is the most dangerous, noting that observations need to be recorded as a condition of employment, and on geography: the most problematic was our 4th building, where the cafeteria and the coffee machines are located.

I wrote a report and showed it to Eugene. He just shook his head.

– Not good. I advise you to send it to Herbert before the meeting, and write: "Here are the preliminary results of the analysis. What statistics should be calculated additionally?" – and sympathetically added:

- But they'll fire you anyway.

However, it worked out. Snow removed my report from the agenda, and supervision over the database was delegated to a young specialist, the same nice lady who discovered an unknown liquid on the table in the analytical lab.

***

Greg Miller has been invited to the next meeting of the Safety Committee. After analyzing fairly minor current incidents, Larry gave him the floor and asked him to talk about his work at the famous DuPont company and how they were striving for "Zero Accidents," an idea that, as is well known, also originated from DuPont. Greg was ready for this question; he had already familiarized himself with the Talbot mantras and cheerfully whistled that "Drive to Zero!" interweaved the entire safety policy, leading to a steady decrease in the number of incidents and increased vigilance at all levels.

- Well, how do you implement your STOP program at DuPont, Dr. Miller? - Greg was confused.

- Uh-uh, the STOP program? Yeah, I heard something about it... I think they stopped it about five years ago... probably as useless, people complained that the inspectors distracted them from work.

Herbert Snow, who was present at the meeting, smiled absently, the line of his moustache slightly curved, and his pink cheeks paled somewhat. He looked at his notebook and left the room. Larry seemed not to notice.

- Thanks, Greg, good luck with your work here in Talbot. You can leave now if you want, or stay - listen: we have another item on the agenda - an analysis of the incident in Texas at the British Petroleum plant, which we are conducting at the recommendation of OSHA, a lot of lessons to learn.

But we already know what happened there. The night shift operators forgot to open the manual valve, and flammable gasoline gradually began to accumulate in the column. There were many other alarming indicators that something was wrong: an unusual temperature profile in the column, excess pressure, an elevated liquid level... but for this, you had to look at the monitors at least, and they went to sleep. As it was written in the report, "... the human factor played a role, people were tired ." What struck me most was that this was the very first launch of the gasoline column after major process overhauls—clearly the result of meticulous engineering—and yet, not a single designer bothered to show up. It was almost poetic, really. Like a theater director deciding the premiere wasn’t worth their time. Why attend the opening night of your own production?

The principle of anonymity, "It’s not the people who are to blame, but the system,” worked, although all the active and inactive persons were known. No one from British Petroleum was prosecuted, several middle managers resigned, and the trade union protected the operators. The Company paid 200 million in fines to various agencies like OSHA and 2 billion in lawsuits.

***

Greg Miller was fired almost immediately after that meeting; I don't know exactly what the reasoning was, but he could have been blamed for not understanding Talbot's core values. Wan Durago stayed at Talbot for three years and, as Greg Collett said, had fun and even remained a member of the Corporate Safety Committee. Larry and Herbert retired at the same time but remained safety consultants. Kevin Massila was demoted from director to senior engineer, which was too much of a shock even for Finn, and he resigned of his own accord. But Gezim Merzini is still working there, as an inspector for the 5-S program.

© Dimus, 2025

Comments